Chilean Government’s Lithium Industry Plan

Likely To Have Major Ramifications on Global Energy Transition

-

June 01, 2023

DownloadsDownload Article

-

The announcement by President Gabriel Boric on April 20, 2023, that private companies will need to partner with the state to extract lithium is the latest sign that the Chilean government is attempting to increasingly control Chile’s mining industry.1 Chile is currently the second largest producer globally and holds the world’s largest reserves of lithium.2 There is currently no immediate substitute for lithium on a commercial scale for the electrification of mobility and the plan, if voted into law, could have a dramatic impact on the supply of a mineral that is critical for the world’s energy transition.

Although Mexico set a precedent in April 2022 by nationalizing its lithium mining and extraction industry, it has relatively small reserves.3 Chile’s plan would have a significantly greater impact on global supply and could entice Bolivia and Argentina, which together with Chile account for about 53% of the world’s lithium resources,4 to follow suit. This could alter the landscape for the supply of critical minerals more broadly, regardless of whether President Boric’s plan becomes law, as the announcement may encourage other countries to accelerate the development of domestic lithium production and, longer term, technologies that do not rely on lithium. On the one hand, the announcement creates uncertainty and increases the risk profile for mining projects in Latin America. On the other, it will likely result in a favorable re-rating and a premium for lithium projects in other jurisdictions. Meanwhile, this development may reinforce China’s strategic position as Chinese enterprises seek to leverage their foothold in Latin America’s mining sector and aggressively pursue investments throughout the battery value chain.

History of Government Involvement in the Mining Sector in Chile

President Boric’s proposal is the latest sign of government intervention in the natural resources sector in Chile

After years of debates around a new royalty regime for copper and lithium,5 the latest signal of government intervention in Chile came on April 20 when President Boric proposed a public-private partnership for future lithium mining, suggesting a move toward the formation of a state-owned enterprise.6

The plan emerged amid growing concerns over the impact of lithium mining on the environment and indigenous communities, as well as a desire to capture a greater share of the profits from the booming global demand for the metal.

To be sure, state ownership and control are not new for Chile, and the country has a history of government intervention in the mining sector. In 1970, President Salvador Allende promised to nationalize copper mining without compensation to the companies operating in the country at the time. The copper mining industry was nationalized soon after his election, with only modest compensation for these companies. Codelco, the state-owned copper mining company, was nationalized in 1976. Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile (SQM), Chile’s leading domestic lithium and industrial chemicals producer, was established as a private company in 1968 and nationalized in 1971 before being privatized by General Pinochet’s government.7

President Boric’s proposal also comes as part of a broader agenda toward increased control of natural resources by governments in Latin America

In August 2022, Mexico’s president issued a decree establishing a new state-owned enterprise (Litio para Mexico) for the exploration, mining and refining of lithium.8 “We are going to nationalize lithium so that it cannot be exploited by foreigners, neither from Russia, nor from China, nor from the United States; oil and lithium belong to the nation, to the people of Mexico,” said López Obrador in a speech addressing the new Mexican lithium plan.9

In April 2017, Bolivia established Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianosin (YLB) as a state-owned enterprise for the exploration, production and commercialization of lithium and other minerals.10 While Mexico’s plan is an outright nationalization of the lithium industry, Bolivia and Chile have so far chosen a middle-of-the- road approach. For now, Argentina, which also holds among the world’s largest reserves of lithium,11 has maintained a market-driven development policy for lithium extraction and continues to grant mining concessions to foreign firms without the requirement for a partnership with the Argentine state.

The Chilean government’s plan could have significant implications for global lithium markets and the world’s electrification in the context of the energy transition

It appears that President Boric’s latest proposal, at least on the surface, seeks to establish public-private partnerships in lithium rather than forcing private companies out. Further, the proposed plan will need to be approved by Chile’s National Congress, that has blocked several of his proposed new laws since his election in 2021 and in which President Boric currently lacks a legislative majority. Most recently, in March 2023, the lower chamber of Congress, the Chamber of Deputies, rejected Boric’s proposed tax reform.12 As a result, achieving major reforms in key industries, such as lithium, will likely be a challenge for his administration.13

Under the proposed plan, Chile may not take immediate control of current lithium mining operations and projects. It seems that existing contracts will remain in place, which should insulate SQM until 2030 and Albemarle, a U.S. company and the other major lithium producer in Chile, until 2043.14

However, President Boric’s announcement signals that Chile may not be open for business in the same way as it has been. The announcement shocked foreign companies and investors and has created uncertainty about the direction in which policy is moving in Chile and the precedent it could set for other lithium- producing countries. In reaction to the announcement, Albemarle sought to discuss President Boric’s plan with Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (CORFO), the Chilean government’s economic development office, and it remains to be seen how the proposal may impact the company’s lithium projects in the country.15

Chile is the second-largest producer of mined lithium (extracting about 39,000 tonnes in 2022, or 30% of the world’s mined lithium) and holds the largest lithium reserves in the world (9.2 million tonnes), representing nearly 36% of the world’s lithium reserves.16 Given its current production and reserves, we see Chile continuing to play an integral role in lithium for the foreseeable future.

We consider that while there will be no immediate threat to supply, the proposal will likely raise concerns among companies throughout the battery raw material and automotive value chain. In our view, those companies could fear that government intervention would disrupt global supply chains and potentially lead to higher prices for lithium carbonate and hydroxide, key materials for batteries used in electric vehicles and renewable energy storage systems.

Will the Chilean Government’s Plan Encourage Countries in the “Lithium Triangle” to Form a Cartel?

The idea of a cartel between Chile, Bolivia and Argentina is not new and comes at a critical moment for the world’s decarbonization efforts

Chile has had a strained relationship with Bolivia since the War of the Pacific in the late 1800s, during which Bolivia lost its coastline and became a landlocked country. Relations between Chile and Argentina have also been affected by border conflicts, mainly in the Patagonia region, but are generally more positive. Despite historical frictions, if President Boric’s plan is approved, some speculate that a common cause could overcome these differences and bring the creation of a lithium cartel between Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, the so-called “lithium triangle,” closer to realization. The three countries together control the majority of the world’s lithium reserves and resources, with Chile alone accounting for over one-third of global mined production.17

A lithium cartel could lead to inefficiencies, delaying of investment or operational decisions, and higher costs. It could also lead to higher and more volatile prices for lithium compounds, as the countries involved could limit production and control supply. In March 2023, President Luis Arce indicated that Bolivia would be open to working with other countries in Latin America to design a common policy for the exploitation of lithium.18

The idea of a lithium cartel is not new but, given the animosity between countries, its actualization is unlikely in our view. However, it is being discussed as a possibility in a region that holds the key to a large share of the world’s future production at a critical moment for the energy transition as governments, investors, automotive companies and other industries accelerate their plans to decarbonize mobility and harness electric storage.

A more direct involvement of governments and highly uncertain regulatory environments in the “lithium triangle” will likely accelerate plans to increase production in other jurisdictions, but supply will remain constrained

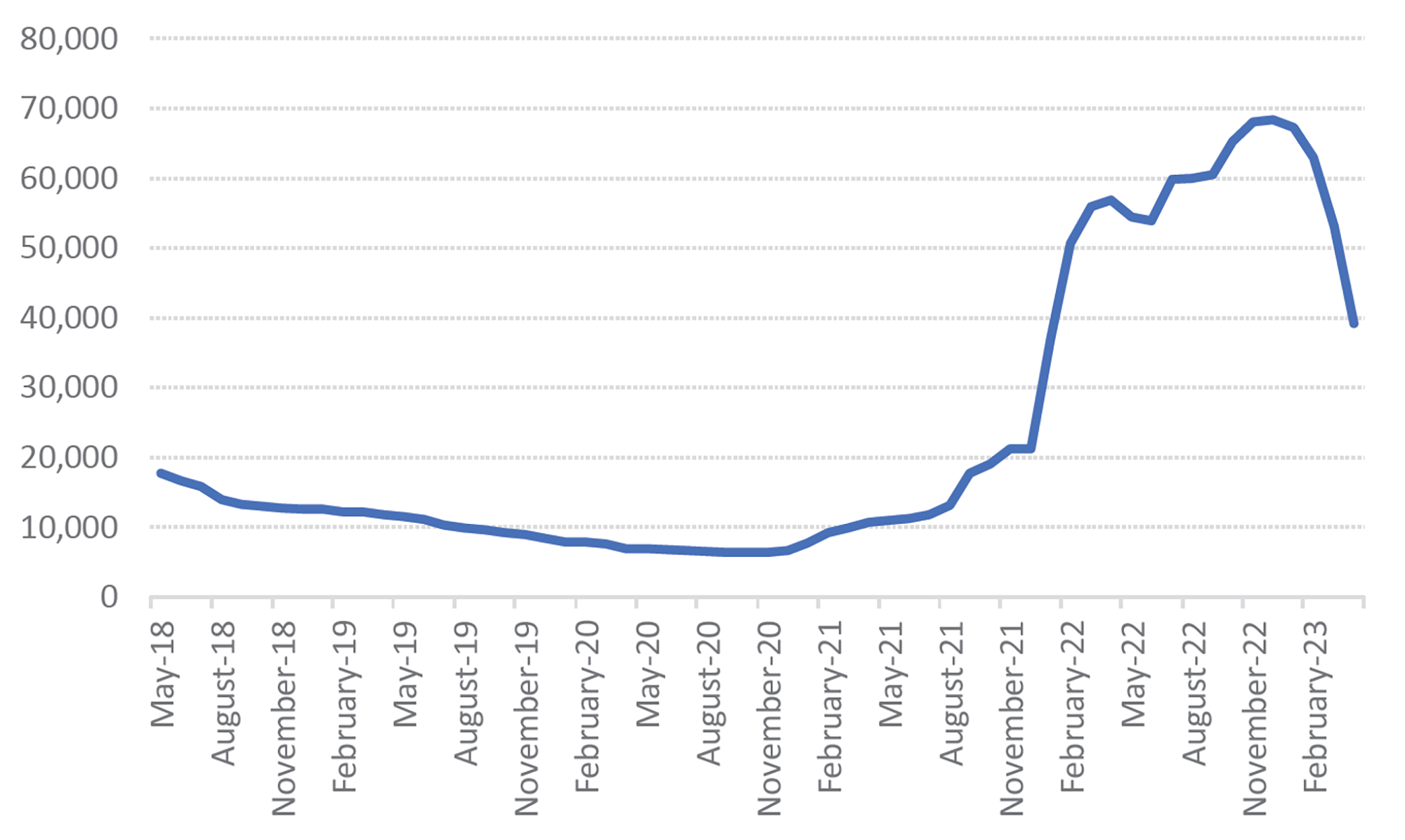

While Chile, Argentina and Bolivia hold a significant portion of lithium resources, other sources of the mineral, such as hard rock deposits, are also widely available in other regions of the world. The increase in prices for lithium in 2022 (see Figure 1) and expectations that supply will continue to lag demand as electric vehicle (EV) penetration accelerates have made marginal projects potentially more economically attractive, particularly with the improvement of processing technologies.

However, lithium is not a scarce mineral and a cartel or any form of nationalization in Latin America will likely incentivize other producers to accelerate plans to develop projects in other jurisdictions, including Canada and Australia, but also the United States and Europe.

Regardless of whether President Boric’s plan becomes law, it has created considerable uncertainty and increased the risk profile for mining projects in Latin America. At the same time, this will likely result in a favorable re-rating and a premium for lithium projects in other jurisdictions.

Even so, the development of new mining projects continues to face significant constraints in other, arguably more stable, jurisdictions. For example, we observe that while there are several lithium projects in development in the Unites States, permitting new mines remains a major obstacle and sets the stage for additional tension on supply and price instability.

Figure 1: Lithium Carbonate Global Average Price (USD/tonne)19

What Will be the Implications Downstream for Cell Manufacturers and Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs)?

Any disruptions to the supply of low-cost lithium in Latin America will have ripple effects through the EV value chain

We consider that supply could be disrupted and costs of production may increase in an environment where governments either directly control or have an influential role in lithium output and development projects.

Higher cost production out of Chile will likely put pressure on global lithium prices and increase end- market costs for electric vehicles to stationary storage. Further, the uncertainty surrounding President Boric’s proposal may deter foreign investment in the region until details about his plan emerge. Any delay in new project development will further increase the near- term supply gap and cause price volatility, potentially affecting the pace of EV penetration.

Toward an acceleration of transactions in the lithium industry

We observe that the increase in expected demand versus supply for lithium had cell manufacturers and OEMs rushing to secure future supply, including via equity investments and long-term offtake agreements. Uncertainty concerning supply from Chile will likely encourage those companies to pursue direct sourcing strategies and further stimulate transactions in the lithium sector.

The industry has already been active with acquisitions. Recently, Albemarle attempted to acquire Liontown Resources (Liontown), a lithium exploration and mining company in Australia.20 In 2013, Tianqi Lithium acquired an interest in the Greenbushes mine in Western Australia.21 In 2015, Ganfeng invested in the Mount Marion Mine.22 These are but a few of examples, and foreign entities continue to aggressively secure rights to lithium in Australia and around the world.

We observe that OEMs have been seeking to invest in lithium companies and projects, as well as new lithium extraction technologies. Among several examples, Ford, Prime Planet Energy & Solutions, a joint venture battery company between Toyota Motor Corporation and Panasonic Corporation, and EcoPro Innovation, signed binding lithium offtake agreements with Ioneer, a developer of a U.S. lithium-boron mine. General Motors announced in January 2023 that it would make a $650 million equity investment in Lithium Americas’ Thacker Pass, thereby also securing an offtake agreement.23 In April 2023, General Motors also agreed to fund EnergyX, a U.S. company developing direct lithium extraction and refinery technologies.24

However, we consider that in Europe and the United States, the lengthy and unpredictable permitting process has slowed and, in some cases, paused the development of new mines that would produce critical minerals, hampering the ability to meet regional energy transition goals. Despite these hurdles, we will likely see increasing interest in domestic mining to accelerate the supply for lithium and other minerals tied to the energy transition.

Threats of disruptions to supply will likely accelerate innovation in developing both additional sources of lithium and technological substitution for the decarbonization of mobility

Amid market conditions characterized by elevated lithium prices and uncertain supply conditions, firms will likely accelerate investments in disruptive innovation solutions related to lithium production and technological substitution.

With respect to lithium production, these investments will increasingly be associated with the exploitation of unconventional lithium resources that seek to provide incremental lithium carbonate supply in an advantageous pricing environment. Chief among these investments are operations that seek to produce lithium as either a co-product (e.g., geothermal electricity) or a primary product whose manufacture is partially subsidized by producing other chemicals (e.g., boric acid, bromine).

In parallel to other sources of lithium, there will also likely be even more emphasis and investments in the development of more efficient production techniques, such as Direct Lithium Extraction.

Further, OEMs will likely increasingly seek to develop alternative technologies to displace lithium use in the electrification of mobility applications. These technologies include investments in sodium-ion batteries with similar performance to lithium-ion batteries and research into hydrogen fuel cell powertrains with comparable zero tailpipe emissions relative to the battery electric vehicle powertrains.

Will Chile’s Proposed Plan Benefit China?

Beyond mining resources, Chinese companies are seeking to invest downstream in EV battery cell manufacturing in Latin America and leverage their position in the mining sector

China’s presence in the mining sector for critical minerals has dramatically increased since 2009, when its government began subsidizing the development of EV technologies.25, 26 Due to insufficient domestic lithium reserves, Chinese companies started investing abroad, including in Latin America, to secure supply.

In December 2018, Tianqi Lithium, a Chinese company that focuses on investing and extracting lithium resources, acquired a 23.77% stake in Chile’s SQM for about $4.1 billion. The deal was immediately met with scrutiny as Chilean authorities, competitors and consumer groups expressed concerns that the agreement would give Tianqi significant power over lithium supply in Chile and pricing worlwide. A Chilean antitrust court eventually approved the transaction.27

However, the country’s National Economic Prosecutor’s Office (NEP) placed restrictions on the agreement, such as the inability for Tianqi to elect executives of its company to SQM’s board of directors and limitations on Tianqi’s access to SQM’s sensitive information. These restrictions were put in place until 2022, with the possibility of renewal for two additional years. In 2022, Tianqi’s executives met with government authorities to lift some of these restrictions. Chilean officials denied the petition, and, in March of this year, Tianqi condemned and appealed this decision.28

In Bolivia, where there are also extensive lithium supplies, the government signed a $1 billion agreement with the Chinese firms CATL, BRUNP, and CMOC and the Bolivian state company YLB to explore domestic lithium deposits in January 2023.29

Beyond mining, the presence of Chinese firms is also expanding downstream in the battery value chain. In 2022, CATL indicated that it was considering several locations in Mexico for an EV battery cell manufacturing plant to supply (at least partially)U.S. customers.30

In April 2023, China’s BYD, the world’s largest electric vehicle manufacturer, indicated that it plans to build a cathode plant with 50,000 tonnes per year capacity for lithium iron phosphate batteries in Chile.31 On April 21, 2023, concurrently with President Boric’s announcement of the public-private partnership for lithium, Chile granted to the Chilean subsidiary of BYD the status of qualified lithium producer, thereby giving BYD access to preferential prices for quotas of lithium carbonates, a key precursor for compounds used in lithium-ion batteries.32

Looking forward, President Boric’s announcement could open the door to further Chinese involvement in the Chilean lithium industry. If local or U.S. companies become concerned over plans for majority state control of existing or future contracts, Chinese companies with more experience with state involvement could ultimately increase their position in, or take over lithium development projects in Chile. These arrangements may involve state-to-state agreements, with China being in a strong negotiating position with Chile.

By investing downstream in countries with free-trade agreements with the U.S., will China circumvent U.S. efforts to reduce its reliance on Chinese producers and ultimately benefit from the Inflation Reduction Act?

The United States has a free-trade agreement with Chile has been in place since 2004.33 This is relevant for U.S. guidelines requiring that battery minerals be sourced from the United States or free-trade countries in order to qualify for tax credits from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).34

The IRA does not preclude Chinese companies from selling battery materials or other critical components produced in countries with free-trade agreements with the United States.

The dynamics of global supply chains and competition for strategic minerals are increasingly complex and will become even more so if government intervention becomes entrenched in Chile and other countries in Latin America. However, political uncertainty is not limited to Latin America, and there are concerns relating to the future of major government programs that have global consequences, such as the IRA in the United States. Certainly, the trajectory of the lithium industry and, by extension, the paths to decarbonization of transportation will remain sinuous.

Footnotes:

1: Cecilia Jamasmie, “Chile to nationalize its lithium industry,” Mining.com (April 21, 2023), https://www.mining.com/chile-to-nationalize-its-lithium-industry/.

2: “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022 – Lithium,” USGS.gov (May 1, 2023), https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022-lithium.pdf.

3: Ibid.

4: Ibid.

5: Bertrand Troiano, et al., “Mining Royalties, Elections and the Constitution in Chile,” FTI Consulting, Inc. (July 29, 2021), https://www.fticonsulting.com/-/media/files/latam-files/insights/articles/2021/jul/mining-royalties-elections-constitution-chile.pdf?rev=6dc4b6db16764a3d8e91bc3f8e12035c&hash=E989613C09536D06F79B7CA1CAE6BAA2.

6: Cecilia Jamasmie, “Chile to nationalize its lithium industry,” Mining.com (April 21, 2023), https://www.mining.com/chile-to-nationalize-its-lithium-industry/.

7: “About SQM; Our History,” SQM.com (May 1, 2023), https://www.sqm.com/en/acerca-de-sqm/informacion-corporativa/nuestra-historia/.

8: Carolina Pulice, “Analysis: Decree adds to doubts about Mexican lithium industry’s future,” Reuters (February 24, 2023), https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/decree-adds-doubts-about-mexican-lithium-industrys-future-2023-02-24/.

9: “López Obrador complete la nacionalización del litio en México,” World Energy Trade (February 20, 2023), https://www.worldenergytrade.com/politica/america/lopez-obrador-nacionalizacion-litio-mexico.

10: “Law No 928: Law of National Strategic Public Company for Bolivian Lithium Deposits – YLB,” IEA.org (May 1, 2023), https://www.iea.org/policies/16654-law-no-928-law-of-the-national-strategic-public-company-for-bolivian-lithium-deposits-ylb.

11: “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022 – Lithium,” USGS.gov (May 1, 2023), https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022-lithium.pdf.

12: Antonia Laborde, “The Chilean Congress deals a strong blow to Boric with the rejection of his tax reform,” El Pais (March 8, 2023), https://elpais.com/chile/2023-03-08/la-camara-de-diputados-de-chile-rechaza-la-reforma-tributaria-de-boric.html.

13: Daniela Cuellar, et al. “A New Constitution, Mining Royalties, and the National Lithium Plan: What’s Next for Business in Chile?” FTI Consulting Inc. (April 27, 2023).

14: “Chile se compromete a respetar contratos vigentes de extracción de litio,” BN Americas (April 26, 2023), https://www.bnamericas.com/es/noticias/chile-se-compromete-a-respetar-contratos-vigentes-de-extraccion-de-litio.

15: “Corfo y Albermale sostienen reunión para abordar estrategia nacional de litio,” Corfo Chile (April 25, 2023), https://www.corfo.cl/sites/cpp/sala_de_prensa/nacional/25_04_2023_reuni%C3%B3n_albemarle.

16: “Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022 – Lithium,” USGS.gov (May 1, 2023), https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022-lithium.pdf.

17: Ibid.

18: Ramos, Daniel, “Bolivia president calls for joint Latin America lithium policy,” Reuters.com (May 1, 2023), https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/bolivia-president-calls-joint-latin-america-lithium-policy-2023-03-24/.

19: “Lithium Carbonate – Global Average ($/tonne),” S∓P Global Market Intelligence (May 1, 2023).

20: Albermale announces proposal to acquire Liontown,” Albermale (March 27, 2023), https://www.albemarle.com/newsalbemarle-announces-proposal-to-acquire-liontown.

21: “Talison Lithium-Update on Tianqi Transaction,” Talison Lithium Limited (February 25, 2013), https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2013/02/25/1363409/0/en/ Talison-Lithium-Update-on-Tianqi-Transaction.html

22: “Mt Marion Lithum Project Offtake and Equity Investment,” Mineral Resources and Neometals (September 21, 2015), http://clients3.weblink.com.au/pdf/MIN/01663485.pdf.

23: Ernest Scheyder, “GM to help Lithium Americas develop Nevada’s Thacker Pass Mine,” Reuters (January 31, 2023), https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/gm-lithium-americas-develop-thacker-pass-mine-nevada-2023-01-31/.

24: “Energyx Recent Press Review: GM Leads $50M Funding Round in Energyx,” EnergyX (April 13, 2023), https://energyx.com/blog/energyx-recent-press-review-gm-leads-50m-funding-round-in-energyx/.

25: Zeyi Yang, “How did China come to dominate the world of electric cars?,” MIT Technology Review | Tech Review Explains (February 21, 2023), https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/02/21/1068880/how-did-china-dominate-electric-cars-policy/#:~:text=Starting%20in%202009%2C%20the%20country,spending%20to%20improve%20their%20models.

26: “Neometals: Mt. Marion lithium project offtake and equity investment,” Market Screener (July 25, 2015), https://www.marketscreener.com/quote/stock/NEOMETALS-LTD-19344222/news/Neometals-Mt-Marion-Lithium-Project-Offtake-and-Equity-Investment-20696728/.

27: Antionio De la Jara, “Tianqi buys stake in lithium miner SQM from Nutrien for $4.1 billion,” Reuters (December 3, 2018), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-chile-tianqi-lithium-idUSKBN1O217F.

28: Leonardo Cárdenas, “Tianqi quiere invertir más em SQM,” La Tercera (June 12, 2022), https://www.latercera.com/pulso/noticia/tianqi-quiere-intervenir-mas-en-sqm/BKRWTAD73VH2TK5D7FSOTLE3HQ/.

29: Joseph Bourchard, “In Bolivia, China Signs Deal for World’s Largest Lithium Reserves,” The Diplomat (February 10, 2023), https://thediplomat.com/2023/02/in-bolivia-china-signs-deal-for-worlds-largest-lithium-reserves/.

30: Al Root, “Watch for the 800-Pound Gorlilla of EV Batteries. CATL Might Build a Factory in Mexico, Report Says.” Barron’s (July 18, 2022), https://www.barrons.com/articles/catl-ev-batteries-north-america-51658147342.

31: Paul Myles, “BYD to build battery component plant in Chile,” TU Automotive (April 21, 2023), https://www.tu-auto.com/byd-to-build-battery-component-plant-in-chile/#:~:text=Currently%2C%20BYD%20supplies%20electric%20buses,lithium%20carbonate%20as%20an%20input.

32: “China EV maker BYD to build $290 million battery component plant in Chile,” Reuters (April 20, 2023), https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/china-ev-maker-byd-build-290-mln-battery-component-plant-chile-2023-04-21/.

33: “Chile - Country Commercial Guide: Trade Agreements,” International Trade Administration (October 1, 2022), https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/chile-trade-agreements#:~:text=The%20U.S.%2DChile%20Free%20Trade,percent%20of%20the%20world%EF%BF%A2%EF%BE%80%EF%BE%99s%20GDP.

34: “Treasury Releases Proposed Guidance on New Clean Vehicle Credit to Lower Costs for Consumers, Build U.S. Industrial Base, Strengthen Supply Chain,” U.S. Department of the Treasury (March 31, 2023), https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1379.

Related Insights

Published

June 01, 2023

Key Contacts

Key Contacts

Senior Managing Director

Senior Managing Director

Associate Director